Ever Given: more than 100 days of ship talk

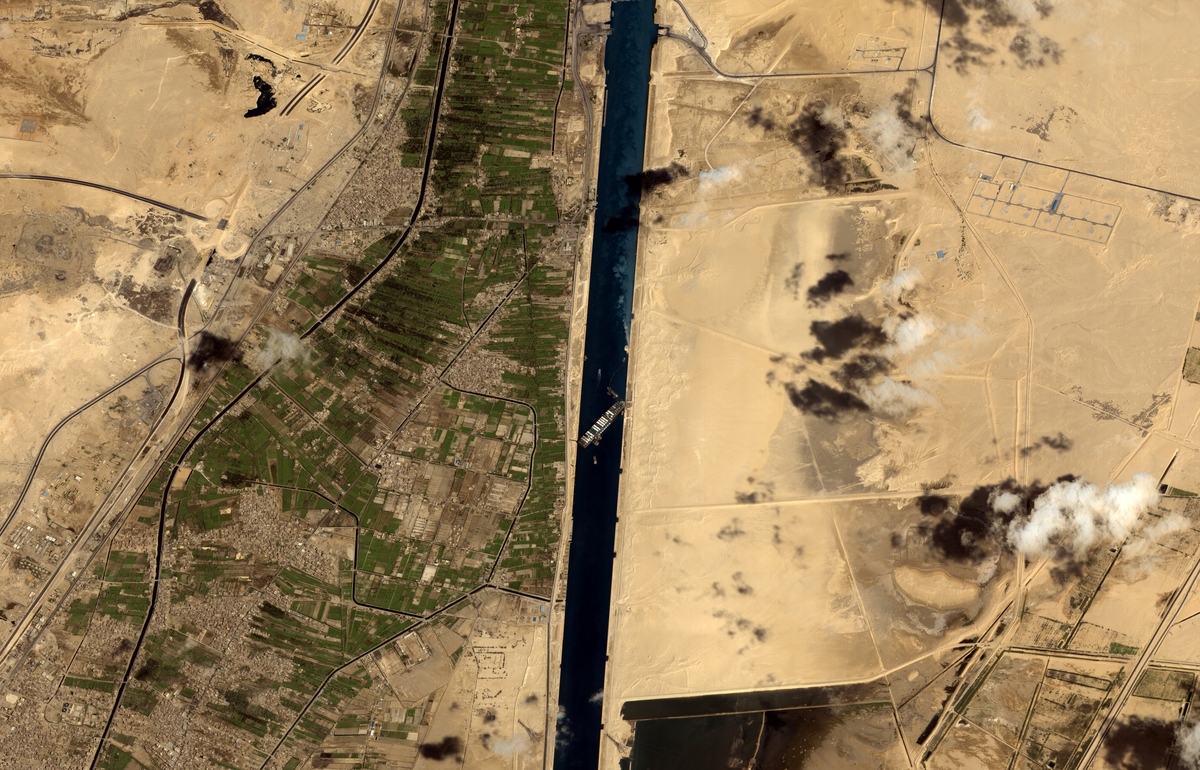

Egypt’s Suez Canal, a narrow, man-made waterway dividing continental Africa from the Sinai Peninsula, made global headlines on March 23 as it got blocked by a massive cargo ship: the Ever Given, a so-called «mega-ship» operated by Taiwan-based Evergreen Marine Corp.

The dimensions of the cargo ship — it is one of the largest in the world — and the way it got stuck — its bow touching the canal’s eastern wall, its stern, the western wall — made for some social media-worthy shots that quickly went viral.

But it soon became evident that the vessel’s blockage was a serious problem not only for the stuck boat itself but for the wider trade artery.

Traffic was halted; the global shipping system, disrupted

The Ever Given was carrying around 18,000 containers from China to Rotterdam that would certainly not reach its destination on time. The other 50 vessels that go through the canal every day had to show some patience while tugboats surrounding the ship made unsuccessful attempts to push it the right way. After efforts of a backhoe digging into the sandbank to free the ship failed, everyone figured the operation could take a while.

As one of the world’s busiest trade routes, about 12 per cent of global trade, one million barrels of oil and eight per cent of liquefied natural gas pass through the Suez Canal each day. While the Ever Given was stuck, 367 cargo ships waited, with nearly $10 billion in trade held up each day of the blockage, and, according to Osama Rabie, chairman of the Suez Canal Authority (SCA), a $14m-$15m hit of the Canal’s revenues per day.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, trade passing through the Suez Canal contributed to 2 per cent of Egypt’s GDP. A lot was at stake.

All sorts of goods were caught up on the vessels, with Asian exporters and European importers affected most directly.

For a week, no effort was strong enough (Image: Getty)

The canal provides the shortest link between Asia and Europe. The alternative, around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, is a far longer, more expensive, and dangerous route. Some companies contemplated taking it, aware of the daunting challenge rescue workers were facing: the container ship is almost as long as the Empire State Building is high (200 metres) and weighs 220,000 tons. It can carry up to 20,000 containers. Clearing the way was never going to be easy.

But on March 29, amid high winds, a sandstorm that reduced visibility, and an unusually high tide, they managed to dislodge it. Almost a week of pushing and pulling had gone by until the Ever Given was finally unbound from the canal – and the canal from the Ever Given. Though only partially.

President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt celebrated on Twitter: “Egyptians have succeeded today in ending the crisis of the stuck ship in the Suez Canal despite the great complexities surrounding this situation in every aspect.”

The Suez Canal Authority said it had been moved about 80 per cent of the way back toward a normal position – 20 per cent was still to go.

Osama Rabie, chairman of Egypt’s Suez Canal Authority – an unusual crisis to manage (Image: Roger Anis/Getty)

“Pulling the rear end of the ship afloat was the easy part, the challenging part will be the front of the ship,” Peter Berdowski, chief executive officer of Boskalis Westminster, the parent company of the salvage team, told NPO Radio 1 in the Netherlands at the time.

“Now we will start working at the front. We do not want to celebrate too early.”

From outside, the blockage continued to be an amusing sight that fuelled a saga of memes. Inside, it was complicated.

Though it didn’t end there.

As the finger-pointing started, these questions lead the battleground

The wind from the south gusted to nearly 80km an hour. Why, at that strength, did Krishnan Kanthavel, the ship’s captain, decide to go ahead anyway? His decision may have been subject to the demands coming from Western consumers: if he didn’t carry on, Kanthavel may have thought, that could cause a delay in the cargo the Ever Given was carrying to Europe.

How safe are ships the size of the Ever Given? Dozens of similar vessels had traversed the Suez Canal in the previous year without hiccups. More than 100 mega-ships currently operate around the world. But there had been warnings: shipping analysts have been saying for years that container ships have grown too big for some ports and canals, becoming a potential safety threat.

Have canals grown accordingly? In order to accommodate bigger ships, wider canals are needed. The Suez Canal was expanded to add a second lane in 2015. The segment of the canal where the Ever Given ran aground in, almost 30km long, was not widened when those works happened. On this note, Egypt has already taken action. The section of the canal where the blockage occurred is being widened and deepened. More powerful tugboats alongside other crucial materials are being added to the equipment of the Suez Canal.

Steamers passing through the Suez Canal in the 20th century. With their dimensions, a blockage like that of the Ever Given would have been impossible. (Image: Getty)

Everything from the bad weather and how it was handled, to the pilots’ experience as well as conversations in the canal’s control tower is being analysed in an investigation that is proving somewhat slow. Following maritime protocols, it is Egypt’s and Panama’s responsibility to investigate. Egypt’s for being the country where the incident happened; Panama’s for the flag the ship flew. Many wonder whether the International Maritime Organization shouldn’t have a bigger say.

Someone’s got to pay for this

The moment the Ever Given was freed, the Suez Canal Authority seized the vessel and its crew in a lake between two stretches of the waterway, the Great Bitter Lake. The waiting boats were finally able to resume their trips.

“Today we will start our plan for all the ships to cross the canal,” said Mohab Mamish, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt’s adviser for the Suez Canal. “It could take around one week to get all ships out of the Suez Canal corridor.”

Now, all those involved could discuss a key matter: who was going to pay for the damage.

After three months of arguing, a formal settlement was agreed upon between the owner, insurers, and Egyptian authorities.

The authorities initially demanded $916m to compensate for losses in transit fees due to the closure and salvage costs, damage to the infrastructure, and reputation. At first, the ship’s owner, Shoei Kisen Kaisha, and its insurers offered $150m, while the Suez Canal Authority had gradually reduced its number to $550m.

The insurer UK P & I Club said in a statement: “Following extensive discussions with the Suez Canal Authority’s negotiating committee over the past few weeks, an agreement in principle between the parties has been reached.”

The amount was not specified but the canal authority gave the GO for the vessel to sail on July 7.

“Preparations for the release of the vessel will be made and an event marking the agreement will be held at the Authority’s headquarters in Ismailia in due course,” Faz Peermohamed of Stann Marine, which represents owner Shoei Kisen and its insurers, said in a statement.

And off went the Ever Given!

More than 100 days after it caught the attention of the whole world, it resumed sailing, straight to the Mediterranean.

July 7: off it goes (Image: Getty)

The Suez Canal blockage has been one of history’s most significant shipping accidents. It has been portrayed with a certain lightness, possibly due to the ridiculousness of the ship’s massive dimensions as opposed to the tugboats’ tiny ones; possibly due to the tough-enough health crisis that has everyone concerned today. That lightness, however, doesn’t prevent the global supply chain industry to look at itself and at the costly delays the blockage led to and ask:

What if something like this happens again?